How to Not Die in The Outback: 10 Tips From An Aussie Survival Expert

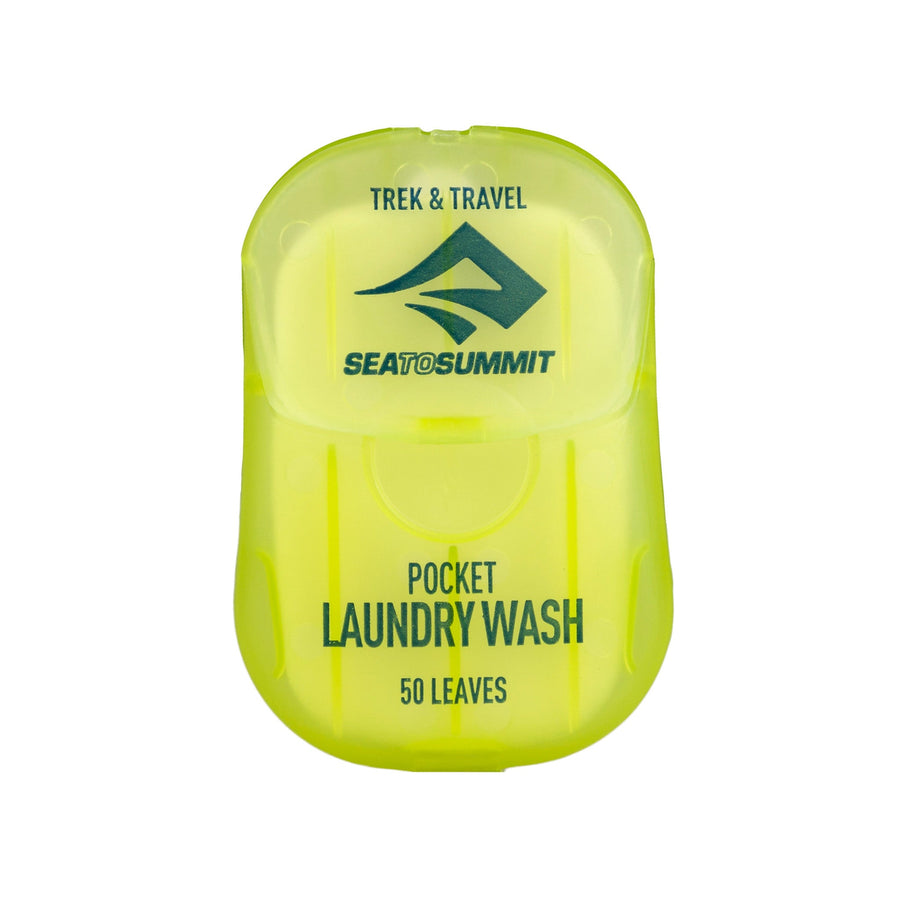

Lit by our head lamps, each of us is handed our survival kit. Not much bigger than a soap dish, this Mary-Poppins-like tin somehow fits 32 lifesaving essentials inside—everything we need to survive in the Australian outback. And everything we need to survive our weekend survival course.

I’ve been spending the past few months researching lightweight and compact gear for an upcoming thru hike—the reason I wanted to brush up on my survival skills—but this palm-sized tin takes the cake.

The kit includes the stock standard survival paraphernalia like fire starting and first aid supplies, and more surprising provisions like a stock cube, bag of tea and a sachet of coffee. Given the tight real estate of the box, it seems odd to have such luxury items. But presumably our instructor, Bob Cooper, one of the foremost experts in outback survival—with Special Forces training and decades spent learning ancient bushcraft skills from indigenous peoples all over the world—knows what he’s doing.

We’re instantly tasked with lighting a cotton pad with a flint. My wrist moves fast striking my flint, yet I can’t get a spark. Everyone has lit their fire already and now they’ve moved on to offering me advice. My embarrassment grows. One of the other two instructors eventually helps me set the cotton ablaze. I guess this is why we’ll be learning four different ways to start a fire in the wild.

With a mischievous grin, Bob gives me a chance to redeem myself, and I’m tasked with lighting the group’s campfire that evening and keeping it alive for the rest of the night. My palms sweat as I brace myself for yet more embarrassment. How will I handle hiking the Te Araroa—a 1800 mile trek through the New Zealand wilderness—if I can’t even light a fire? But the fire takes, the group settles into the warmth and by the end of the night my confidence grows.

My confidence continued to grow over the weekend and after two and a half amazing days, I’d gained more than navigation, fire-starting and snake awareness skills—I felt more connected with the land and the ancient civilizations that lived on it sustainably for more than 60,000 years. As I braided string I’d made out of Umbrella Grass, and nibbled nuts and seeds foraged from the scrub, I realized how two dimensional my view of the Australian bush had once been.

I’ve collected some of my newfound knowledge and funneled it into 10 handy tips to remember if you find yourself in a not-so-lucky situation in the outback.

1. HAVE A CUPPA

‘A little taste of home,’ Bob says as he begins to explain why a cup of tea (or coffee) is more than just a tasty beverage.

While Australia might be home to a good chunk of the world’s most venomous spiders and snakes, most people die from making bad decisions. From heading off into the desert without adequate water supply or any sense of a back-up plan.

A hot drink is the first step to channeling your fight or flight response into something more constructive. It can also help boost morale when all seems lost. That feeling we love that comes from our morning coffee can help save your life in a survival situation. It might bring you back to earth long enough to make you realize you’re walking in the wrong direction.

‘In the unforgiving environment of the outback, where temperatures can reach as high as 122 degrees Fahrenheit, dehydration can take you in hours.’

When you don’t have an Aussie breakfast tea handy, boiling the local lemongrass or melaleuca leaves can also make a tasty cup. After learning the indicators for spotting poisonous plants—and how to test potentially edible ones—we soon learnt how almost every plant was useful to humans, either for a cup of tea, a tasty snack, various medicinal purposes and more.

2. HYDRATE

Bob has a lot of stories about other people’s demise. And a lot of personal experience with near-death scenarios (what we learn to call ‘lucky Bob’ stories around the campfire). It comes with the territory as a survival instructor, I suppose.

As Bob imparted many of these forensic bedtime stories to us, a recurring theme became apparent. Almost all of them died from dehydration. Not the 173 species of snakes in Australia, or venomous spiders. Good old-fashioned dehydration.

In the unforgiving environment of the outback, where temperatures can reach as high as 122 degrees Fahrenheit, dehydration can take you in hours. We can go three to four weeks without food, but only a day or a few days without water.

‘We dehydrate from the head down,’ said Bob. Meaning most people lose their ability to think pretty quickly, eventually succumbing to ‘dehydration dementia’. According to Bob, people have even unknowingly committed crimes against other people in this compromised state of low sodium. So it’s worth paying attention to how much water your fellow comrades are drinking out in the wild.

‘Conserving energy can be the difference between life and death. This is the moment to have that cup of tea—to stop you running into the endless outback without a plan.’

The first step for avoiding dehydration is to always bring enough water, however, even the best of us have ignored our mother’s instructions and left the house with a limited water supply. If you’re stranded and you’re getting thirsty, the easiest way to find a water source is from your very own car. Simply turn the air conditioner on, get a bowl and put it in that spot your car always makes its embarrassing little leak. The water coming from your air conditioner is clean and drinkable.

3. DRINK, DON’T SIP

You’re stuck in the desert with one liter of water left. What would you do? Would you make it last as long possible or drink it in a day? I assumed the best course of action is to conserve my resources, but I soon discovered that sipping water is a mistake many have made. People have been found dead of dehydration with a water bottle that’s three-quarters full.

‘The liver and the kidneys are the pirates of the body,’ Bob explains. ‘You need to drink at least one cup of water (250ml) at a time so it can hydrate your brain and other organs.’

Drink a liter in four cups, not 200 sips. You’ll keep your brain going long enough to come up with a plan.

4. DON’T SWEAT IT

We’re fueled by adrenaline, we’re geared to leap into action—ready to unleash everything we’ve learnt watching Bear Grylls. But conserving energy can be the difference between life and death. This is the moment to have that cup of tea—to stop you running into the endless outback without a plan.

FIND WATER—BAG A TREE!

People respire, trees transpire. Find a non-toxic tree in direct sunlight, cover one of its branches with a plastic bag, making sure there’s no air coming in or out, and the tree will sweat drinking water. It can save your life.

In the desert you can lose one liter of water every 30 to 60 minutes through perspiration and respiration (yep, still harping on about dehydration—it’s that important). Bob tells us about a Special Forces exercise he was put on, where his group were dropped in the desert with no access to water and no idea how long they’d be out there. Three long days the team stayed in the arid area, incredibly dehydrated, but surviving. They did so by laying under a rocky outcrop in the shade and limiting almost all their activity (except for grumbling about their senior instructor—nothing brings you together like finding a common enemy), surviving by squeezing some drinkable water out of ground succulent plants.

5. GET USED TO YOUR SHADOW

Make it second nature to keep an eye on your shadow. It can help a lot with navigation. Keeping your shadow in the same position to your body for around twenty minutes at a time lets you know you’re walking in a straight line. After the twenty minutes, the sun will move and so will the angle of your shadow.

You can even use a ‘shadow stick’ to find north, then other directions you need, using nothing but sunlight, three sticks and your two eyes.

Bob tells us yet another desert demise story and explains how they could have survived if they’d waited to see what direction the sun was going, rather than leaving the car in the midday sun and walking off the wrong way.

6. BECOME A NIGHT OWL

Your body loses half the water at night than in the day. If you must travel, sleep in the shade during the hot days, and travel by moonlight. This will also keep you warm during cold desert nights.

We put this into practice one night and crashed through the brush with nothing but a glow-in-the-dark compass and our night vision. Rather than being scared by the darkness (and my abnormal fear of serial killers) I found the whole experience oddly serene. It was far easier to focus on putting one foot in front of the other with the lack of distractions that full sight can bring. Or maybe I was just enjoying how beautiful the stars were out of the city.

7. FIND YOUR WILSON

Whether you’re talking to a washed-up soccer ball or a stick that looks like it has a nice personality, speaking out loud is an important part of keeping your cool in a survival situation. Saying ‘I’m going to be ok,’ actually does make you feel better. Saying ‘I could really use some help right now,’ helps too. Talking about what you’re doing, or about to do, keeps you calm and focused. And the best part about being stuck alone in the wilderness, means nobody is there to think you’re crazy for talking to yourself.

8. DON’T GET BITTEN

‘The best way to not die from a snake bite, is to not get bitten,’ Bob imparts in his usual common-sense way. Meanwhile, his assistant, Ann, brings out their ‘darling’ Death Adder, Darth Vader, and places him gently on a pile of leaves outside (with a long snake handling tool, of course—he is one of the deadliest snakes in the world). ‘Snakes are shy—they don’t want to bite humans,’ she explained. ‘They only bite out of fear.’

And it’s true. Almost 90% of reported snake bites are a result of someone trying to catch one. Most likely without shoes on.

She places darling Darth lovingly back in his box and then grabs her ‘babies’ Honey and Bruce-ina, the friendly (and not dangerous) pythons. Soon, all the coo-ing over these reptiles brings down the group’s collective anxiety and we all sit waiting patiently for our turn to hold a python as we learn about snake safety.

Fire covers almost all our survivalist needs—warmth, morale, signaling, cooking, light, protection and so much more.

Wearing appropriate footwear, the right gaiters or loose long trousers is the best way to avoid a snake bite. In Australia, snakes’ fangs are short and designed to kill small animals. They’re just too short to do much damage to humans. Even Bob, who has probably had more near-death experiences than hot meals, has never been bitten on the skin by a venomous snake. Though he’s had a near miss or two (lucky Bob).

If you do get bitten, it’s not a death sentence, so long as you have three compression bandages with you. It takes 45 minutes for the snake venom to make its way through the lymphatic system and into the blood stream. With the correct compression bandaging, that 45 minutes can turn into as much as 20 hours, which should be enough time to get to hospital.

You can watch this video to see how it’s done.

9. BECOME A FIRESTARTER

This time I’m in a race against my fellow survivalists to not be the last one to light my fire. I work my bow across the stick to make enough friction to create a glowing ember. One by one the group managed to make a fire until it was just myself and one other person. With the entire group watching.

It’s not surprising that the ‘friction fire’ is the last activity of the weekend. I’m about to call it quits when smoke begins to appear and a small ember rears its head. With shaking hands, I place it into a little nest made of soft dead grass and blow on it until the flame appears—then I hold it high like an Olympic torch as the whole crowd cheers. Progress.

Luckily, not all fire is as time consuming as the drill and bow method. In our handy Bob Cooper survival kit, we’ve got several different ways to make a fire without matches. Outside of the box, however, there’s dried kangaroo poo everywhere. Black gold. Place one of these pebbles under a magnifying glass (which is also in our survival kit) and it will ignite in seconds.

Fire covers almost all our survivalist needs—warmth, morale, signaling, cooking, light, protection and so much more. Having the ability to make fire in a variety of ways is not only lifesaving but gives you that caveman confidence boost you didn’t even know you needed.

10. HARNESS THAT FEAR

The weekend was over and if we wanted to hear any more ‘lucky Bob’ stories, or learn any more lifesaving skills, we’d need to find them in his book Outback Survival. As we sat around our final campfire of the weekend, Bob reminded us that you could harness almost everything to your advantage—even fear.

Fear is healthy, it releases cortisol, adrenaline and glucose, all of which will keep you going in a survival situation.

Yes, fear is healthy as long as it’s balanced out with knowledge.

‘The first time you practice navigation shouldn’t be when you’re lost in the bush,’ Bob shared.

‘The first time you put a compression bandage on, shouldn’t be when someone’s just been bitten by a snake.’

Bob wished me luck on my upcoming hike and told me he hoped he doesn’t hear about a string of wildfires popping up along the New Zealand trail. Although I won’t be getting bitten by snakes, or walking in the desert, I can already envision the countless ways I’m going to put this course to use as I tramp along for the months to come.

ABOUT BOB COOPER

For over 30 years Bob has honed his survival skills by learning from many traditional cultures. His experiences include living for extended periods with Aboriginal people in our Western Desert, sharing bushcraft abilities with the Bushmen of the Kalahari in Botswana also with the Lakota Sioux Indians in Dakota and jungle time with the Orang Asli people in Malaysia.

He has instructed Special Forces Units, conducted survival courses throughout Australia, lectured with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Service on survival in the Mexican Desert and delivering wilderness lessons in the UK.

Bob has also organized many projects throughout Australia, from social adventures with movie stars and other international celebrities to personal development courses for Youth at Risk.

In 2000, National Geographic America filmed Bob conducting his advanced survival courses in the television series True Survivors which featured on the Oprah Winfrey Show. More recently, he has participated in two documentaries with the BBC in the UK and a segment on 60 Minutes in Australia.